Everyone is talking about the total eclipse of the sun that will happen this year on August 21, which will be visible in the United States. It will pass through Oregon, Idaho, Montana, Wyoming, Nebraska, Kansas, Iowa, Missouri, Illinois, Kentucky, and in the South — Tennessee, Georgia, North Carolina and South Carolina. In northeast Georgia, some areas will be in total eclipse, and some in partial eclipse.

Of course, solar eclipses have been documented since recorded history, and this is not the first solar eclipse seen in Georgia. The only one I remember was in 1984, but before the internet, before television, and even before everyone had radio, an eclipse that was visible in the south, particularly in Alabama and Georgia on May 28, 1900, was really the one to see!

That eclipse was not visible in the northern part of Georgia, but was visible only in the central part of the state. On May 22, 1900 the (Milledgeville) Union Recorder (p. 6 c.2) told readers that “no other total eclipse of the sun will occur in this country until 1918,” and this May 28th eclipse

Will be total in Milledgeville. The fifty-mile wide strip of totality will enter the United States in southern Louisiana, passing over New Orleans, grazing Mobil, over Montgomery, and Columbus, within twenty-five miles of Atlanta, near Macon, Augusta, Columbia and Charlotte, and over Raleigh and Norfolk. —- As many photographs as possible will be taken. Central Georgia and Eastern Alabama are regarded as especially fine places for observation —–.

Several months before the eclipse was to take place, astronomers from across the nation began planning for the event and for their trip South. Newspapers ran articles citing particular astronomers with their comments on several things, including routes they proposed to take to Georgia. As early as May 1, 1900, the (Milledgeville) Union Recorder (p. 1 c.3) quoted Professor W. W. Campbell, of the Lick Observatory in California, that his

eclipse expedition proposes to locate in central Georgia, possibly in the Forsyth, Barnesville and Thomaston region. —- My assistant from here Mr. C.D.Perrin[e], and I expect to reach Atlanta about April 28th, with two tons of scientific apparatus and supplies preceding us by freight train. We hope to establish camp by May 2nd, remain there until about June 14th…..it will be the experience of a lifetime — .

Crocker Eclipse Station, Thomaston, GA; illustration in “The Crocker Expedition to Observe…” Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific v.12 no. 75 p.175-184 (Oct. 1, 1900); provided by NASA Astrophysics Data System.

In The Albany Weekly Herald, May 26, 1900 (p. 8 c.1), an article that appeared in the May issue of McClure’s Magazine was discussed. It quoted Professor Simon N. Newcomb, an astronomer, on how one would prepare to see the “progress of the moon across the disc of the sun” without using the more traditional smoked glass — and gave his thoughts on why photographs would be taken.

if an ordinary spyglass is reversed and the large end pointed toward the sun a picture of the eclipse will be thrown on a piece of paper or cardboard held a few inches below the lower end of the instrument. This —– gives a picture of the phenomenon as clear as a photograph. He says that photography will be used to discover any hitherto unobserved appearance about the sun or the moon during the eclipse, and calls attention to the fact that by the aid of photographs, many stars not hitherto discernible, have been located.

It was an article and a photograph I ran across (“Eclipse Will Be Observed by Experts At Siloam, GA.” Atlanta Constitution May 22, 1900 p. 9) with the mention of “mammoth double photographic telescopes,” that prompted me to enter the name a Professor Charles Burkhalter into my database of Georgia photographers, because I include visiting photographers.

I found out via the article that this was the” Chabot observatory Dolbeer eclipse expedition” and John Dolbeer of San Francisco was paying for the expedition.

On further research I found that Charles Burkhalter wrote an article about this particular trip, “A Popular Account of the Chabot Observatory-Dolbeer Expedition to Siloam, Georgia May 28, 1900.” It was published (along with one by W.W. Campbell and C. D. Perrine of the Crocker Expedition) in Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific (v. 12, no. 75; Oct. 1, 1900; pp. 169-175).

Burkhalter’s double photographic telescopes used in Siloam, GA; unidentified photographer, Atlanta Constitution May 22, 1900 p.9

Burkhalter was in Siloam five weeks. In his article he noted that many of those in the town “considered this expedition ‘the biggest thing that ever happened to Siloam!'” The people of Siloam “fully sustained the great reputation of the Southern people for hospitality —-” In a humorous aside he noted that “I had a camera with me that at once became very popular. —- business would have been brisk if I had had the time to attend to it.”

After he returned to California, the September 1900 St. Louis and Canadian Photographer noted on page 430, that the photographs Burkhalter had taken in Georgia

demonstrated beyond a shadow of a doubt the success of this new method of astronomical photography. The negatives that were taken have been developed into the best photographs of the corona of the sun that have ever been produced. [his] device controls the exposure of the different rays. The exposure of the inner portion of the corona which has given the best result is 4-100 of a second. The outer portion receives an exposure of eight seconds.

As he was making his trip to Georgia, Burkalter found himself traveling in the same rail car with the two astronomers from the Lick Observatory, Professors Campbell and Perrine, mentioned above.

Crocker and Perrine’s expedition was financed by William H. Crocker of San Francisco, and they selected Thomaston as the place to locate their equipment. They arrived on April 30th, selected a site, and soon erected a wooden tower, a pyramid, within another to support a five-inch lens and protect it from any wind. They also set up “a complete dark room, six by ten feet, with water pipes.” A portion of the Crocker Expedition set-up is seen in the reproduction, (the first of the two) above.

Seven astronomers from as far away as Utrect and Leiden, Holland volunteered to serve the Crocker eclipse expedition, at their own expense, and seven additional assistants from Thomaston, including Mayor James R. Atwater, offered their services. In their article in Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific (v. 12, no. 75; Oct. 1, 1900; pp. 175-184, following Burkhalter’s), Campbell and Perrine noted, possibly referring to MIT astronomers, that

we could not follow the practice of the Eastern parties in taking the plates home for development in cool dark-rooms. It was necessary to develop at Thomaston. The week following the eclipse was very hot, both day and night. The dark-room was uninhabitable by day; but after ten o’clock at night, by the liberal use of ice, the temperature of the room could be brought down to between seventy and seventy-five degrees; and the development was carried on between that hour and daylight.

As a result of this expedition, the [Lick] Observatory possesses a large number of very beautiful and very valuable photographs of the eclipse phenomena — A number of very fine small-scale photographs of the corona were obtained with the shorter telescopes —–Several varieties of plates – single and triple coated, slow, medium, and rapid–and exposures from short to overlong, were tried.

The North Polar Streamers of the Corona; exposure 16 seconds, with the 40-foot camera. Crocker Eclipse Expedition, Thomaston, GA; illustration used in “The Crocker Expedition to Observe…” Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific v.12 no. 75 p.175-184 (Oct. 1, 1900); provided by NASA Astrophysics Data System.

Two plates were developed at once in the closet under the stairs of Mr. [Clay] Fillingham’s house; the remaining eight were taken to Professor Barnard, at Yerkes Observatory and to Secretary Ziel, at home [California] for expert development. I began picking up my instruments, leaving the village four days later —-.

Burkhalter wrote that “My stay in the Sunny South was made so pleasant that the name of Georgia is synonymous with friendship, hospitality and good will.” He also thanked, and named, those persons in Siloam who assisted him, including a “Mrs. Robinson, of Greensboro, who made drawings of the corona.” Hers is the only name of a Georgia woman I have come across doing anything related to the 1900 solar eclipse.

Harrison W. Smith and his custom-made camera, May 1900; illustration in Technology Review, vol. 2, no. 3, July 1900. p. 209.

The Eclipse Expedition of the Creighton University, of Omaha, Nebraska, were also stationed in Washington. This expedition was composed of astonomer-professors from Catholic universities and colleges, led by William F. Rigge, S.J. With less funding and staff than his colleagues at MIT, Rigge was able to get needed help from the professors of astronomy in other Catholic “sister colleges” — two from St. Louis University, and one from Xavier College in Cincinnati. The group was housed in “an elegant little pastoral cottage” on the grounds of the St. Joseph’s Orphanage and Academy on Washington’s west side.

Because Creighton’s student observatory was “not equipped with special eclipse instruments,” and because what they had was not portable, he made do with other instruments. The instruments used turned out better results than Rigge expected. He wrote:

While the rest of my party had erected their cameras in front, or east of the cottage, I took up my station on the walk halfway between the church and the residence, where, as I had planned, I was absolutely alone and entirely unbiased by the doings of others. Afterwards, when I realized that my observations were better than I had anticipated, I engaged Mr. Wiley G. Tatom, the Surveyor of Wilkes County, to connect my station with that of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology at the southern end of the town.

For Rigge’s March 1901 article “The Eclipse Expedition of the Creighton University to Washington, Georgia” in Technology Quarterly, vol. 14 no.1, he compiled a comparison of times Observed by Creighton University and by Massachusetts Institute of Technology, as well as several other comparisons of data gathered by the two expeditions stationed in Washington.

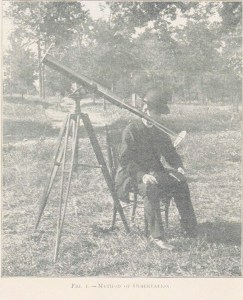

William F. Rigge, S.J. at his observation station, Washington, GA, May 1900; illustration used in Mach 1901 Technology Quarterly, vol. 14 no.1 , page 9.

Dr. Geo. D. Case watched the eclipse from the Masonic building with the idea of making a report to the naval observatory at Washington. His record shows that the eclipse began at 6:31 to the minute. The time of totality was [an] even fifty seconds by a stop watch. This shows that some of the scientists were wide of the mark in their calculations for this point. They all agreed that the period of totality in Milledgeville would not exceed ten seconds. From the beginning to the ending of the eclipse was 2 hours, 18 min. 25 sec.

Although Milledgeville citizens and others certainly enjoyed their time “in the eclipse,” it appears that some people were frustrated by not being able to make the scientific observations themselves, with their own astronomical equipment. An editorial appeared in the Dalton North Georgia Citizen, on June 7, 1900 (p. 4 c. 1) referring to The Atlanta Journal, who

Hit the bull’s eye geometrically in the center with the following:

Let us hope that by the time another total eclipse is visible in Georgia, there will be a college in this state sufficiently well equipped to take scientific observations. — we had not even a field glass, comparatively speaking.

I believe they got their wish, a lot has changed in Georgia education since 1900. I loved my class in Astronomy at Georgia State University. We gazed at the heavens atop the old Kell Hall, or was it Sparks? Well, it was a long time ago, but it was very memorable!

Today GSU is a member of the CHARA (Center for High Angular Resolution Astronomy) Consortium, and GSU is the owner and operator of the CHARA array. There are now eight astronomical observatories in the state of Georgia that feature telescopes used for astronomy research, the state has ten astronomy clubs, and planetariums are located all over the state.

Total eclipse of the sun, January 24, 1925, photo montage by F.E. Hewitt’s (Corning, NY); courtesy Swann Galleries, New York (Auction, May 21, 2015, #2385, Lot 109)

Until next time, when I hope to share more interesting Georgia-related photo facts with you, go make memories — and images.

Chauncey Barnes, in Mobile, took a daguerreotype of an eclipse of the sun in 1854 and displayed it as a curiosity in his gallery. Glad to know that these rare moments attract photography attention . .

Frances

Yes, there are some wonderful images out there of both solar and lunar eclipses made since the beginning of photography. The 1900 group was not at all the first, but astronomy photography had made quite a lot of progress since the 1888 eclipse. That one was only seen as partial, not total eclipse in California, yet the astronomers managed to set up 15 separate stations 100 miles north of San Francisco. I could not figure out how to relate that tidbit to my GA piece, and now I have!

I really enjoyed this post. It’s fascinating to see pictures and read about an eclipse more than a hundred years ago. I probably shouldn’t have been surprised, but I was surprised that people knew ahead of time that an eclipse would occur back then.

I have never understood those predictions either, but they had been doing it for a long time prior to 1900 – it is all pretty amazing isn’t it? Thanks for reading.

Lee